Addiction is a word that evokes a complex web of emotions, judgments, and beliefs. For some, it represents the heartbreaking decline of a loved one. For others, it triggers anger, blame, or confusion. But one question continues to divide public opinion and shape treatment policies: Is addiction a disease or a moral failing?

The Traditional View: Moral Failing.

For much of history, addiction was seen as a character flaw, evidence of weak willpower or moral deficiency. Society often branded people with substance use issues as irresponsible or self-indulgent, believing that they could stop if they truly wanted to. This stigma led to punishment rather than treatment, and incarceration rather than care.

From religious teachings to early psychological models, the underlying message was the same: addicts choose their path and must suffer the consequences.

The Modern View: A Chronic Brain Disease.

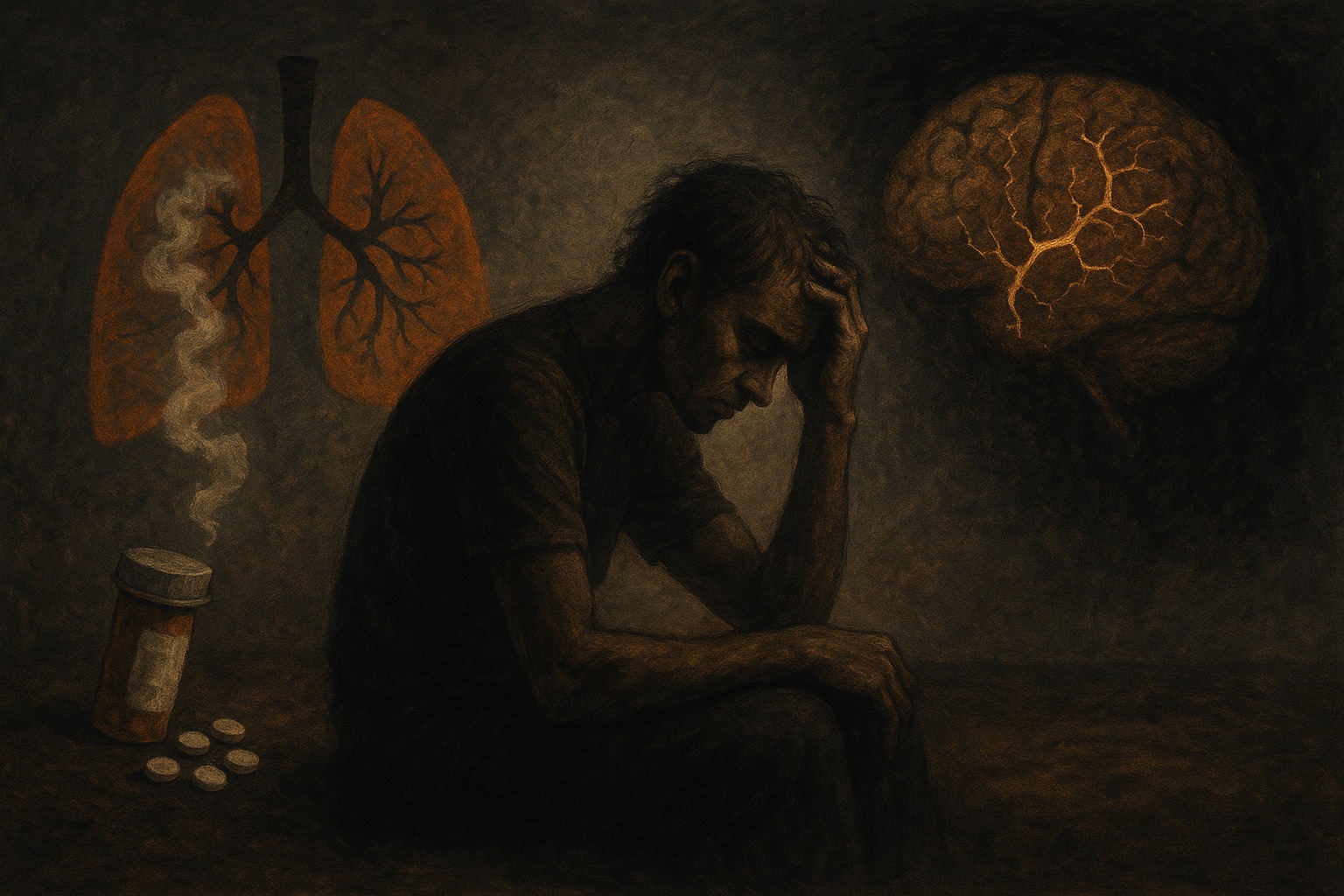

In recent decades, science has dramatically reshaped our understanding of addiction. Major medical organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), now classify addiction as a chronic brain disease.

Here's why:

- Neuroscience shows physical changes in the brain. Repeated substance use alters the brain’s reward system, impairing judgment, impulse control, and decision-making.

- Genetics matter. People with a family history of addiction are at a higher risk, pointing to hereditary influences.

- Environmental factors contribute. Trauma, poverty, mental illness, and social isolation all increase vulnerability.

- Relapse rates are similar to other chronic diseases. Just like diabetes or hypertension, addiction often requires long-term management and multiple interventions.

In this model, addiction is not a choice, but a disease that hijacks the brain's functions. People don't choose addiction any more than they choose cancer.

Is It Really Either/Or?

Labeling addiction solely as a disease or moral failing may oversimplify a deeply delicate issue.

- Choice plays a role, at least initially. The first drink or drug use is voluntary. Once addiction sets in, the brain is altered, and self-control diminishes dramatically.

- Personal responsibilities still matter. Recognizing addiction as a disease doesn't absolve individuals from accountability. Treatment is most effective when individuals are actively engaged in their recovery.

- Moral framing can worsen stigma. Viewing addiction as a moral failure can lead to shame and silence, preventing people from seeking help.

- Disease framing can empower recovery. When people understand addiction as a health condition, they’re more likely to pursue evidence-based treatment, and society is more likely to support it.

What the Research (and People in Recovery) Say.

Studies consistently show that people recover better when they're treated with compassion, offered comprehensive care, and supported through social systems. Peer support, therapy, medication-assisted treatment, and stable environments are far more effective than punishment or guilt.

People with lived experience also stress that recovery isn’t about excusing behavior, it’s about understanding what drives it and what can help change it.

Conclusion: A Human-Centered Approach.

So, is addiction a disease or a moral failing? The science leans heavily toward disease, but the full answer is more human than clinical.

Addiction is a complex interplay of biology, environment, psychology, and choice. It's both a health issue and a personal struggle. When we treat it as such, without shame and judgment, we pave the way for recovery, dignity, and healing.

Let’s replace blame with understanding. Let’s see addiction not as a moral failing, but as a public health issue that deserves compassion, science, and support.